Spaces at Biennale di Venezia 2018

An updated version of the Spaces built for Seven Mechanical Architectures, bigger and better.

Customer:

Atelier Blumer – Biennale di Architettura 2018 Venezia

Challenge:

Create a new version of Space, bigger, lighter and more reliable to survive the five months of the Biennale with minimal servicing in less than two months.

Year:

2018

Learning from experience

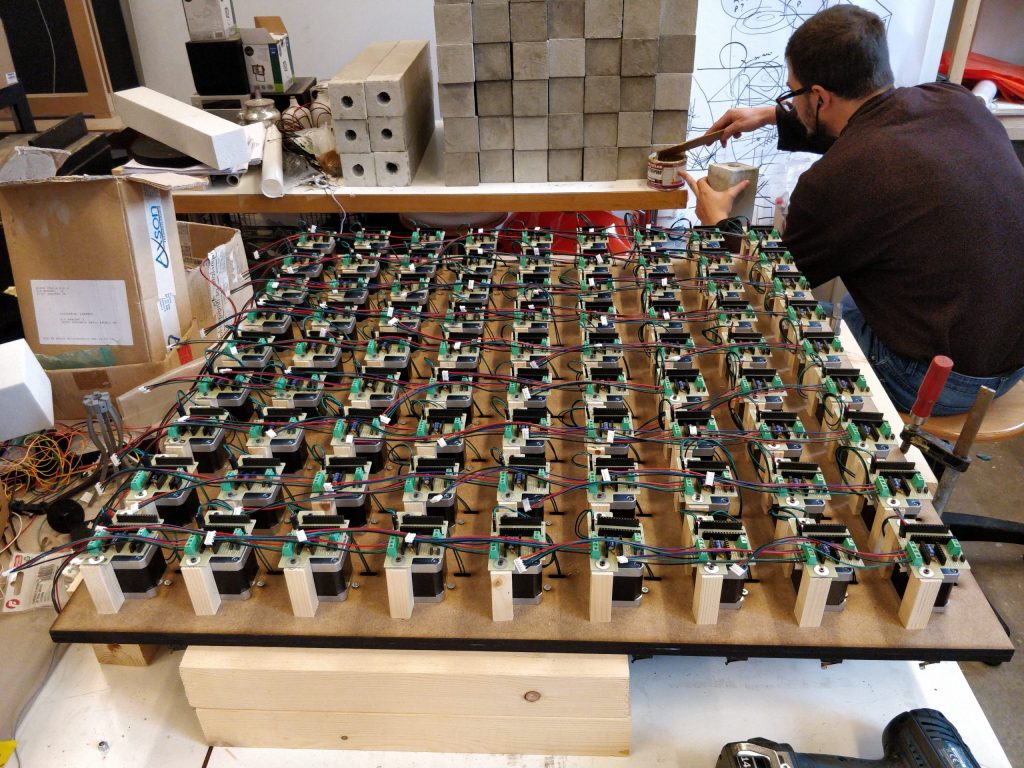

The first iteration of Space was built with quite some freedom given to the student in the design process. This time we had a very limited time to create the installation and a more streamlined process had to be put in place. The stock left from the initial set of installations didn’t allow us to go for another 11×11 matrix and we had to fall back to a 9×9 matrix, fixing defective boards to get to the total of 81 motor drivers.

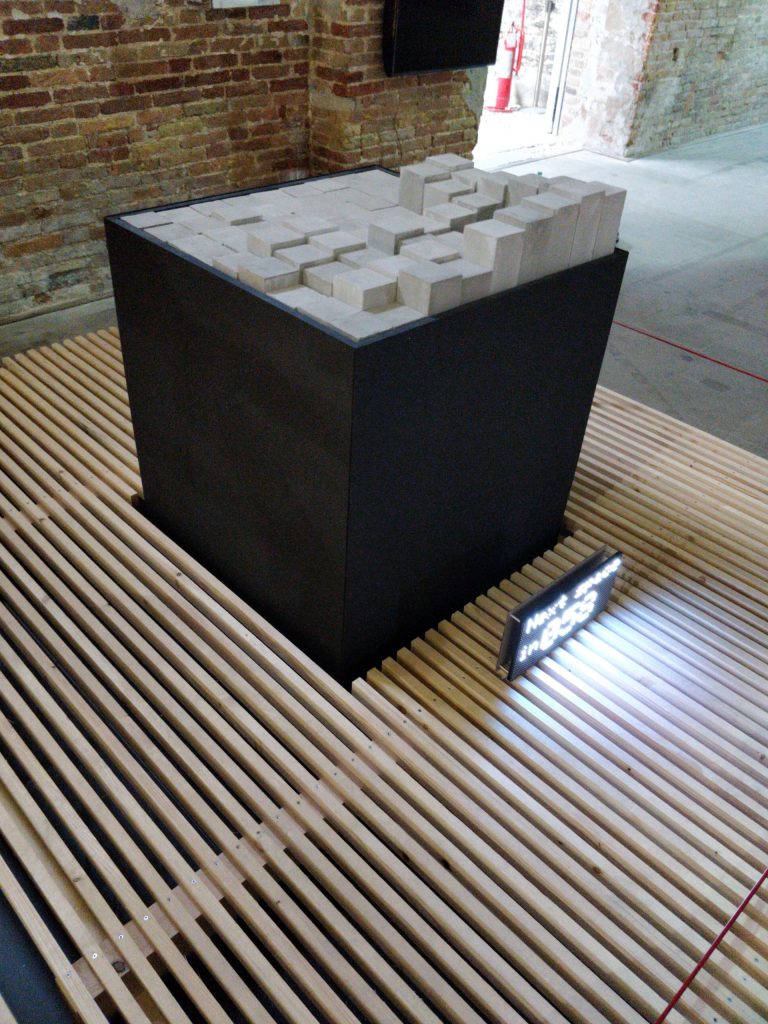

The overall design was updated. We switched from threaded bars to leadscrews and nylon nut blocks; the very heavy wooden columns were redesigned and we decided to use high-density foam with a bigger size (10x10cm). To give it an architectural look we painted the grey foam with grey cement so that the whole set of columns looked like concrete. I was pretty sure it would work, but we had to fight some resistance from the others that thought it could wear out quickly exposing the foam. That would have been possible, but grey foam and grey coating would make any scratch difficult to notice.

The change in the columns material and the bigger size – 9x9x60cm per column – made the whole design reach a size of 85×85 cm and 120 cm of height.

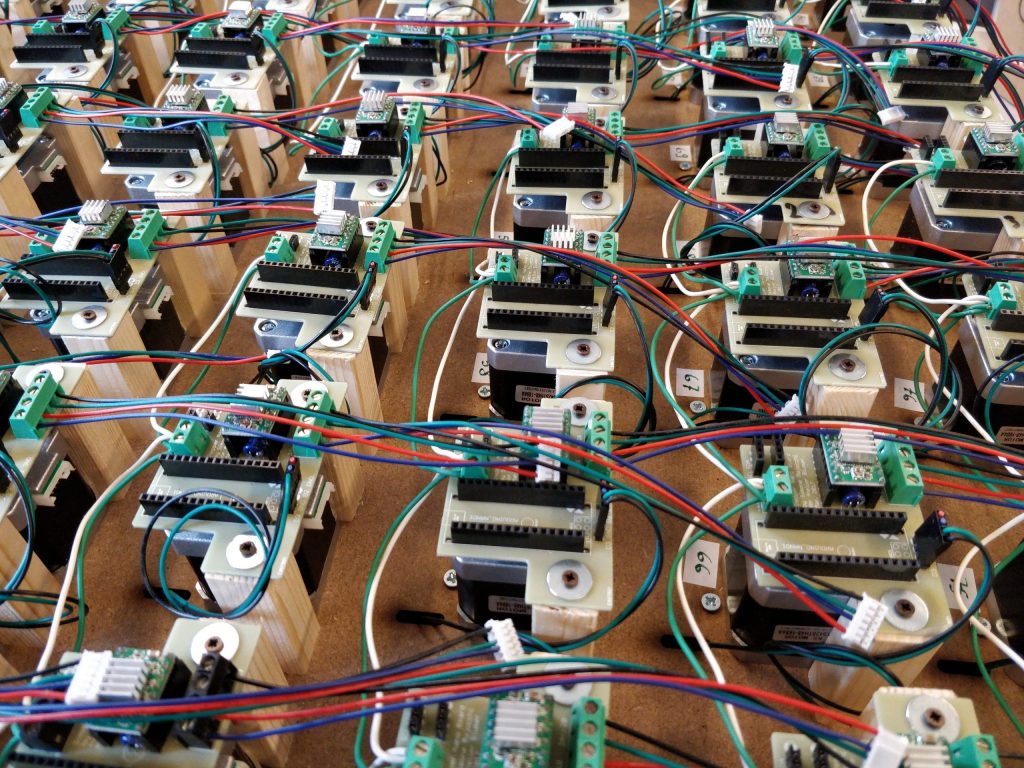

One of the most critical parts of the old design was the connection between the motor shaft and the threaded bar: not very reliable and prone to disconnection. Having enough time and budget, this time we adopted the flexible shaft couplers that allowed to connect and disconnect easily every lead screw.

From chaos to order

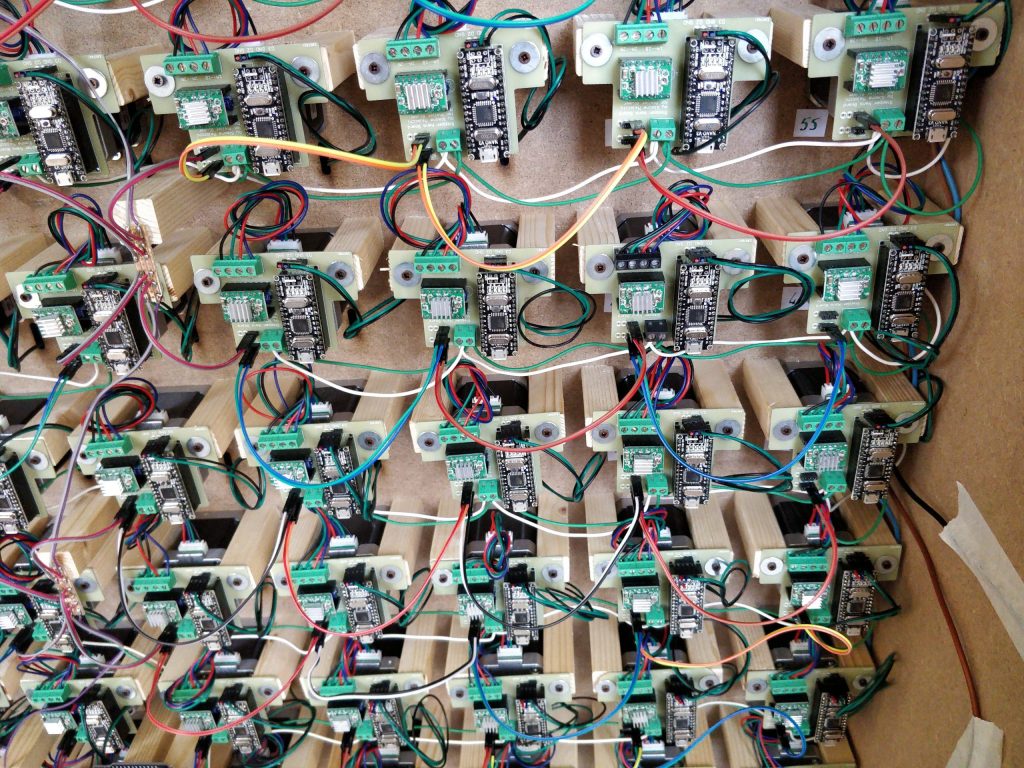

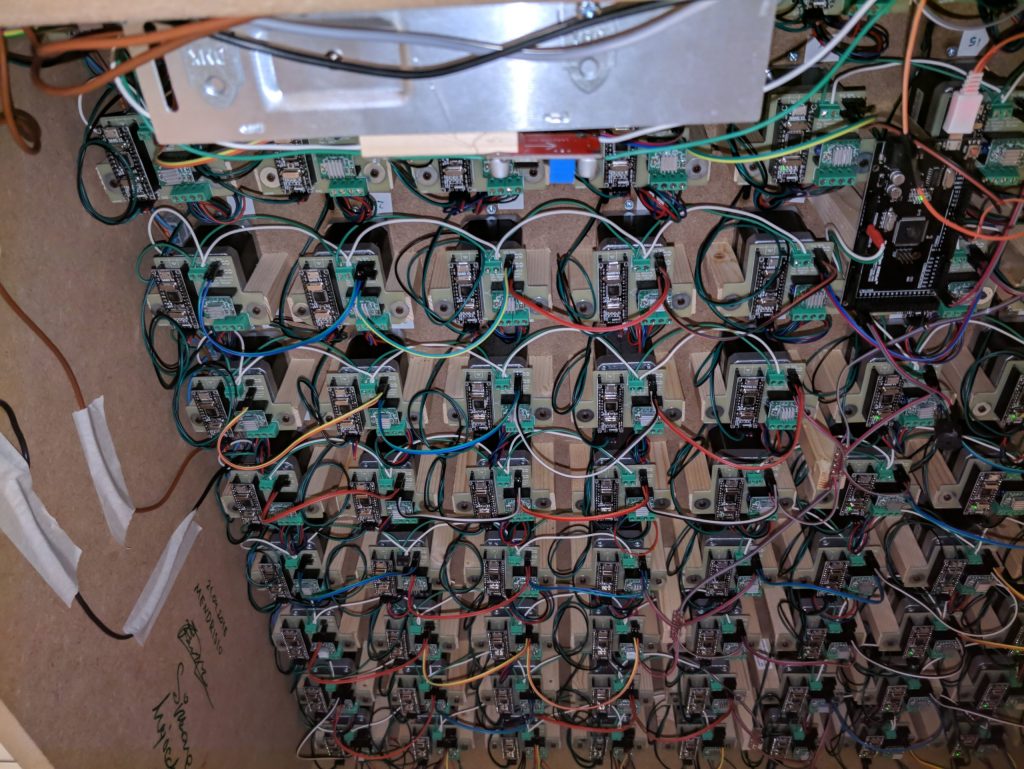

The first version of space was really chaotic due to the very limited space available. More space between the motors meant the ability to place the controller boards in a much more serviceable way and everything looked way more clean and professional. The 20mm MDF panel supporting the motors was laser-cut with all the holes necessary, making the assembly a simple and error-proof process. On one side we had the shafts, the couplers and the microswitch; on the other side we had the motors, the two supports and the controller board. A cut in the board was used to pass through the microswitch cables. Every motor came with a four-pin cable, but for our design, we needed just half of it because we had screw terminals on the PCB. The half that wasn’t used was recycled to connect the microswitch to the PCB. We did our best to use or reuse every part that was supplied.

The core of the design was the board with all the motors and it quickly became problematic for its handling. The MDF itself was a few kilograms, but with the 81 motors installed it jumped to around forty kilograms. We had to develop a clamping system to keep it vertical and allow cabling and assembly.

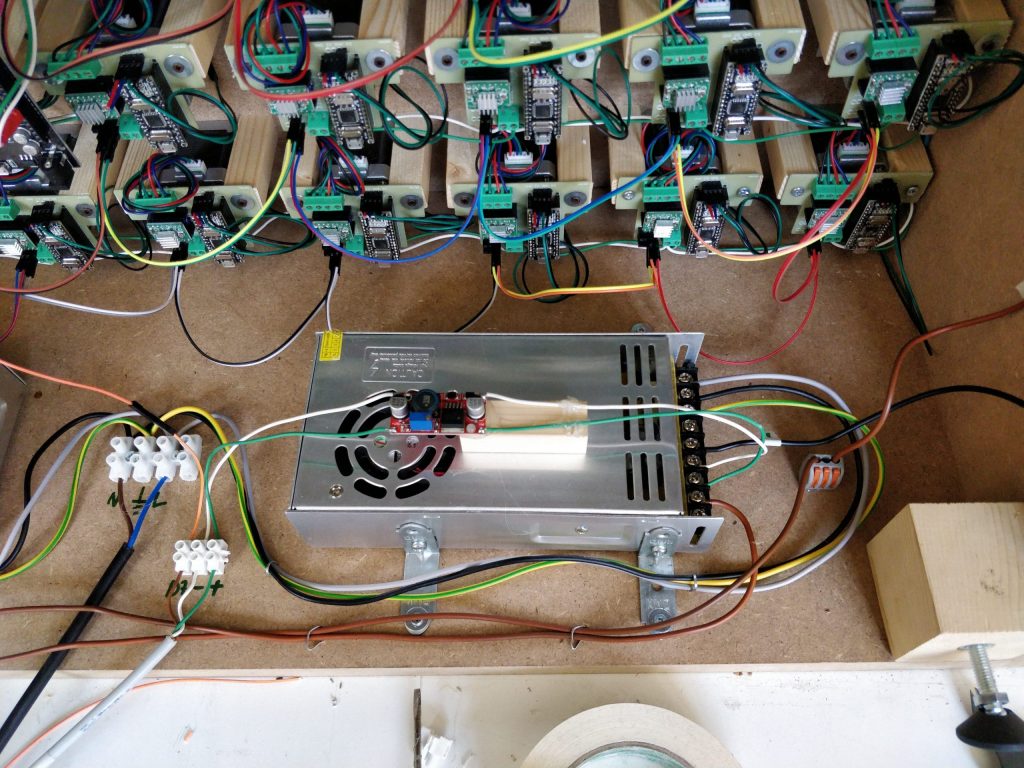

From 1000 to 1700 lines of code

Initially, we were told that it was possible to service the installation if something broke or failed, but as we got closer to the opening of the Biennale, the chances of being allowed to do any repair became from little to non-existent. The machine had to have built-in resiliency and this is why the code of the driving module and the one of the main controller – the one generating the patterns and sending the commands to all the motors – grew with additional routines and tests. The motor controller had new tests for granting its proper zeroing and it was also capable of detecting if the column was not moving as expected. The main controller was equipped with a heartbeat detector – a Nano board -, capable of resetting the whole machine if something got locked up in some unforeseen loop or state and the heartbeat wasn’t received in 20 seconds. The power supply group was also equipped with a little relay board that cycled through a power ON – OFF – ON sequence so that all the boards got properly reset. Last but not least important was a change in the communication protocol between the controller and the motor boards. In the first version, the controller was waiting for all the motors to be available: any stuck or lost board made the whole system to hang. In this version it was possible to have one or more motor board not to respond, a situation that is different from a “busy” reply. This machine was capable of creating the spaces even if one or more motors/columns were temporary not working.

Another addition was a display that was showing “next Space in …” countdown: as a choice, every space generated was visible for 120 seconds, to let the viewers look at it carefully, decoding the type of structure and possibly taking a picture. In this way, every visitor was aware that Space was creating new landscapes every 120 seconds.

I had to travel a few times to Venezia to iron out the last bugs and fix some resiliency issues, but at the end, when the Biennale opened to the public, everything was working as expected.

For the next five months the machine was doing its job from 10 am to 6 pm, resting every Monday. Nothing critical happened even if a couple of columns went dead at some point. If you didn’t know, they just never took again part of any pattern generated.

Space was at the end of the amazing Wall installation, the one that made thin walls of soap and that caught the imagination of so many visitors.

Now this machine is somewhere in the basement of Accademia, back in Mendrisio, waiting to be recycled into some new device if some student decides to look at it and find inspiration for something new. So far no one contacted me to get information on how to use the motor modules.I recently got back in touch with the team and they confirmed that they will contact me if someone needs to reuse something.

On my side, I still have a few leftover PCBs populated with the electronics. I used them to create other projects that involved stepper motors and I am quite proud of the solution I developed back then: it was used to drive at least 230 stepper motors in different installations and it will still be part of new ones if needed.